What is it that has us tapping our foot along to a well-known tune? How does our foot know when to tap? How do the performers stay in time with each other? What keeps the music pushing on, note by note, no matter who is playing it or what is being played?

“The best way to explain pulse - something which has no written or physical presence - is to relate it to the natural and tangible pulse of our heartbeat.”

The answer to all of these questions is pulse. When a piece of music begins a pulse is set and will continue until the end of the piece. The very best musicians can keep the pulse consistent and clear, thus allowing their audience to distinguish the pulse for themselves and be carried away by it.

In the opinion of many - including my own - pulse is the most fundamental aspect of any performance, as it is what allows the audience to connect with what we are playing. If the pulse is changed too suddenly or becomes interrupted then the flow of the music is broken. Any excitement or character that has been built up by the use of phrasing, dynamics or other means is lost and cannot be retrieved. Because of the deep-rooted nature of pulse in music, it is something which I place a lot of emphasis on when teaching.

Introducing the concept of a musical pulse

The best way to explain pulse - something which has no written or physical presence - is to relate it to our heartbeat. Our hearts give us a natural and tangible pulse which can be heard and felt. When we are calm or relaxed our heartbeat is slow. If we are excited or afraid it quickens. A surprise will make our hears "jump", whilst a grave disappointment will make them "sink". The heartbeat is also essential to our survival; if our heart stops then so do we.

By naming the pulse as a "musical heartbeat" it becomes easy to understand as a musical concept. It makes clearer the nature of a musical pulse, all of the ways that a pulse can change the character of a piece and its importance to the continuity of the music.

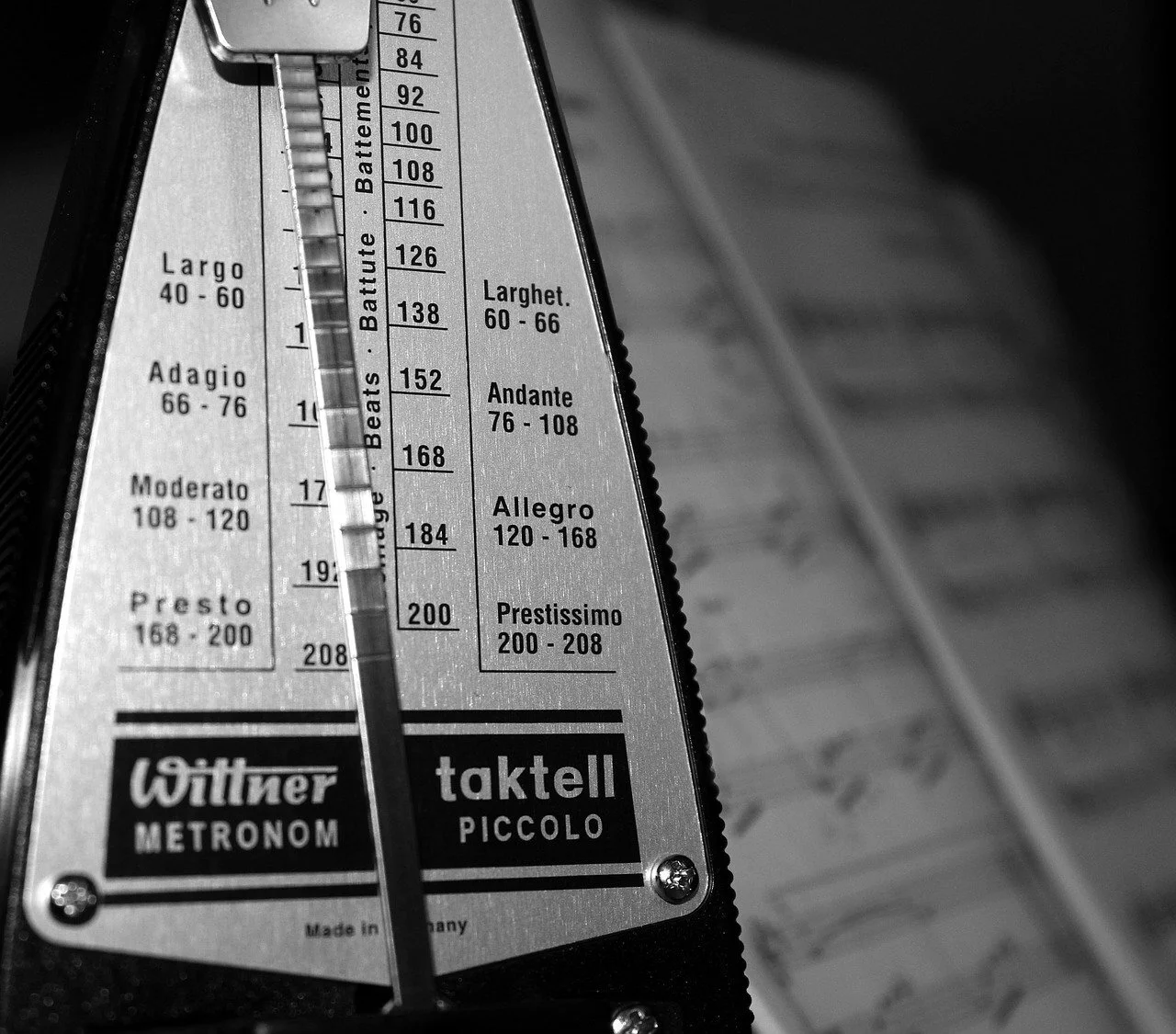

Metronomes

“By setting the metronome to a slow enough tempo so as to allow the pianist enough time to locate where he or she must next play, the whole piece can be played easily with a consistent pulse.”

The importance of using a metronome in lessons and in practise is paramount. It is very easy to learn a piece up to a standard which it can be played with all of the correct notes, dynamics and articulation. However once a piece has reached such a standard, when the performer plays along to a metronome it becomes fragile and often falls apart in the first few bars.

The opening bars of Beethoven's Hammerklavier (Op. 106).

Careful targeted practise of a piece when learning it can so often fragment the music to the extent that it becomes difficult to transition from one chunk to another. It is these transitions that make music challenging. A pianist learning Beethoven's Hammerklavier sonata (Op. 106) may be able to play a second inversion B-flat major chord perfectly well in his left hand, however he may have more difficulty preceding it with a semiquaver B-flat two octaves below the original chord. So while it is true that he can play the individual notes of the Hammerklavier, it is only when he tries to connect them that problems arise.

This is where the metronome comes in. By setting the metronome to a slow enough tempo so as to allow the pianist enough time to locate where he or she must next play, the whole piece can be played easily with a consistent pulse.

Some will argue that extensive use of a metronome will render a performance too "metronomic", however I do not believe that metronomes are to blame for this. While it is true that it would be detrimental to most performances to play the whole piece at a rigid, inflexible tempo, it is up to the performer to introduce an appropriate amount of rubato where appropriate, as well as observing given tempo changes such as accelerandos and ritardandos. In practise the metronome will help you build a fluent and secure performance. More than anything else a metronomic recital is a symptom of a lack of musicality on the part of the performer.

Rhythms and cross-Rhythms

Once students have established a reliable internal pulse they can begin to play distinguishable rhythms. Often in lessons teachers will bend the truth a little to make their point more clear. An example of this is when introducing different notations: a crotchet is usually defined by the teacher as a "one beat note", a minim a "two beat note" and a semibreve a "four beat note".

This is, in fact, only correct if the time signature we are playing in has a four on the bottom, i.e. when one beat is defined as a crotchet. If there were an 8 on the bottom of the time signature (which defines one beat as a quaver) then a crotchet becomes a two beat note, a minim a four beat note and a semibreve an 8 beat note.

“A crotchet is usually defined as a “one-beat note”, a minim a “two-beat note” and a semibreve a “four-beat note”. This is, in fact, only correct if the time signature we are playing in has a four on the bottom, i.e. when one beat is defined to be a crotchet.”

Such a small distortion can be seen as a fair trade-off in early lessons where compound time is a concept reserved for a lesson far in the future. However I feel that it can cause unnecessary confusion between beats and note values, so I prefer labelling a crotchet as a "one count note". It may be a small difference, but as a "beat" has its own separate application in music it is a difference I am keen to emphasise.

Aside from this minor point, there is rarely any difficulty introducing different note values. I spend a lot of lesson time doing rhythm games with students - either clapped or played on one note - to reinforce the values of each notation. Since the introduction of composing to lessons beginner students are sent away with a task to compose a piece using all of the note values they have learned for further emphasis.

Where difficulty often arises is when cross-rhythms are encountered. This is the playing of two groups of notes with conflicting rhythms, for example, a group of three notes played in the same time as a group of two notes. The mind at first has difficulty processing the two separate groups; it is the musical equivalent of patting your head and rubbing your stomach.

The above graphic illustrates how a complex rhythm such as four against three can be counted in 12 quavers - the lowest common multiple of the two groups. In this example the top part would be counted 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12, and the bottom part 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12.

One way around this is to choose a sentence to say that matches the offending rhythm. "One-cup-of-tea" fits very well with rhythms of two against three. For more complex patterns such as three against four, the passage can be counted in twelve, with one hand playing three notes playing on beats 1, 5 and 9, and the other hand playing four notes playing on beats 1, 4, 7 and 10.

This method of using the lowest common multiple of the two rhythms is well served by practising slowly with a metronome. As the speed increases, the brain will become more accustomed to the unfamiliar stresses of the cross-rhythm and will eventually be able to play it without any aids.

Once my students can play a scale fluently hands-together they are instructed to learn it as a cross-rhythm. For example, if the left hand plays in groups of two and the right in groups of three, the scale will reach its peak with the hands two octaves apart (assuming they started a single octave apart).

The same is true if one hand plays in threes and the others in fours; the hand that plays in threes will end up playing three octaves, whereas the hand playing in fours will finish the scale after four octaves.

An illustration of how the sentence "one cup of tea" fits the rhythm of two against three. T=Together, R=Right, L=Left.