- Try deliberately emphasising the first beat of each bar when playing your pieces to get better at clapping the pulse.

- Practise singing along to scales and arpeggios so your voice has solid reference points during singing tests.

- If you see/hear any articulations in singing tests then try to sing them for some easy marks.

- Consider the character of any pieces you are playing and what parts of the music lend that character.

The first exam session of the year is nearly upon us, introducing a brand new syllabus from ABRSM which contains as varied and engaging a selection of repertoire as we have come to expect. With a refreshed syllabus every two years we have been treated to a huge selection of pieces over time, and with a planned update to the scales and arpeggios in 2021, there is plenty to keep piano students on their toes in future exams.

“Aural tests are examining the listening skills that are essential for good musicianship.”

Further to last week’s post on sight-reading, this week I have turned my attention to the other exam staple: aural tests. Like sight-reading, aural tests rarely undergo any fundamental changes within the exam syllabus. The reason for this is that at all Grades they test the listening skills that are essential for good musicianship.

At lower levels, these skills are as basic as clapping the pulse of a piece, while at higher grades candidates must identify chord progressions and cadences. For many students the scope and challenges of these tests are a daunting prospect, however, if they are given some attention in the lessons before an exam then aural tests need not be a cause for concern.

Become a good musician

What is exactly is meant when we talk about good musicianship? While your mind may jump to an image of a virtuoso pianist in mid-concert, it is not the playing of the instrument that makes a good musician. Rather, the skills that we come to rely on begin at a very early stage, ideally from the very first lesson.

The reason why it is important to consider what skills make us good musicians, is that it is entirely possible to pass a Grade 1-3 aural test without any wider understanding of how these tests fit into the music-making process. The world of aural is much deeper and richer than is suggested by the tests alone, and students who are unable to appreciate this will inevitably struggle when progressing to higher grades.

Pulse

The first - and arguably most elemental - of these aural skills is the ability to feel the pulse. This is something that has to written or physical presence and is merely felt by performer and listeners alike. The best way I can explain pulse to someone who is a total stranger to the concept is to make it comparable to a heartbeat. Our bodies are given a natural and tangible pulse by our hearts which can be both heard and felt.

Early grade aural tests require the candidate to clap the pulse to a short excerpt of music. When practising this test with students who do not know what a pulse is, the student will usually try and clap the rhythm. The difference between the two is that the pulse is an underlying constant, whereas the rhythm is a dynamic and changeable pattern of notes that actively contributes to the character of the music.

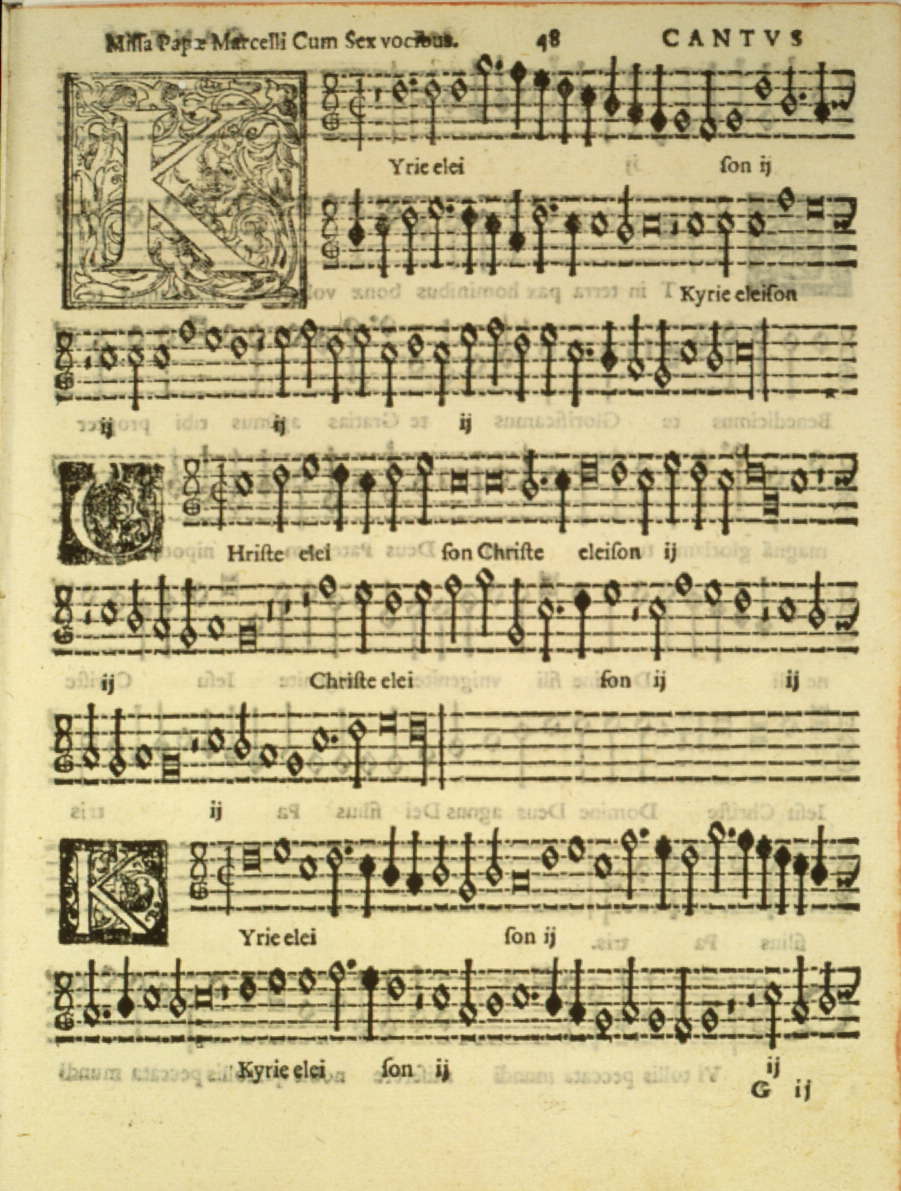

A page of Medieval sheet music. There is no time signature; each beat has the same emphasis.

Time signatures: Defining the metre

Students are asked to give a louder clap on the so-called “strong-beats” and identify whether the music is in 2, 3 or 4 time. These questions are about the time signature, something that has been a part of music since the Renaissance period.

Time signatures give the music strong and weak beats, with the first beat of each bar being the strongest. This is what you must listen for in the exam. The examiner will make an effort to play the strong beats with greater emphasis. To train your ears to pick out strong beats try deliberately emphasising the first beat of the bar in your pieces.

Deciding whether the music is in 2, 3 or 4 time is straightforward if you have identified where the strong beats are during your clapping. If you have been successful at this it is simply a question of counting the number of beats in each bar. As an example, if a piece has 1 strong beat and 2 weak beats then the piece will be in 3 time.

One question that is asked of me frequently is how to tell the difference between two time signatures that sound the same, for example, 2/4 and 4/4, or 6/8 and 12/8. To answer this I ask the student why the composer has chosen to write their music in 4/4 rather than 2/4. By comparing two pieces in these different time signatures we can see that pieces with more beats in the bar tend to have longer phrases. Listen out for long or short phrases in your exam; if you notice that the strong beat is occurring frequently then that suggests 2 beats rather than 4 beats in a bar.

Your Voice: The Hidden Link

A recent study found that only one in twenty people are truly tone-deaf, and yet when I follow up on a new enquiry for adult students they often inform me that this is the case. The scientific term for “tone-deaf” is amusia, and it refers to a person who cannot differentiate between pitches or follow even the simplest tunes. After the first lesson is taught my students will find that they are not, in fact, tone-deaf, and many of them possess greater musical perception than they were previously aware.

“Our singing voice can actually help guide our fingers to the correct notes. Many pianists can be heard humming on their recordings as a means to aid their playing.”

Everyone has the ability to sing and it is practiced in almost every culture around the world.

I asked myself what the reason behind this frequent self-diagnosis could possibly be, to which it seems that when someone describes themselves as tone-deaf they are actually referring to their singing voice. Everyone has the ability to sing and it is practised in almost every culture around the world. For musicians, the voice is the hidden link between the notes on the page and the music we play.

As pianists, we are very fortunate in that we are able to easily access our singing voice whilst playing. The advantages of this are often not immediately obvious to someone who is unaccustomed to incorporating their voice into their practise, however, they are real and plentiful. Strange as it may sound, our singing voice can actually help guide our fingers to the correct notes. Many pianists can be heard humming on their recordings as a means to aid their playing. Singing trains our ears which in turn tell us what we expect to hear when playing.

“Singing trains our ears which in turn tell us what we expect to hear when playing.”

It is for these reasons that singing forms a part of every ABRSM aural test, from Grade 1 to Grade 8. No matter which grade you are taking, there are some general principles to have when preparing for the singing part of the aural tests:

Practise singing along to scales and arpeggios. They act as solid reference points when sight-singing.

Listen carefully to the tonic triad when the examiner plays it, it will help your singing voice assume the correct tonality.

When the examiner plays the starting note sing it mentally and hold it in your mind until you are ready to begin.

When singing intervals mentally sing up and down the scale until you arrive at the right note. Arpeggios will also be helpful with this.

Pay attention to articulations. They are included in every singing test from Grade 1, either on the page if sight-singing or played by the examiner if echoing a phrase. If you include them then you will earn some easy marks, regardless of the quality of your singing.

Identifying Character in Music

The final question of the aural test asks that you listen to a short excerpt of music and describes key features of the piece. To begin with, the features asked about are limited to dynamics and articulation; as students progress through the grades these grow to include tempo, phrasing, texture, structure, style, period and character. It is a daunting list that requires students to have a wide knowledge of musical works.

“Simply by having awareness of the many musical features that a piece has beyond a cluster of notes you will become more musically literate.”

The best way to prepare for this part of the exam is to listen to as much music as possible. Don’t just stick to one composer or one genre, try listening to music from as many sources as possible. You may not enjoy everything you hear, but - if you listen attentively - you will form an opinion of it.

Consider the character of any pieces you are playing. Describe it like you would a person.

It is also worth considering these features in pieces you are practising. What about the dynamics and phrasing gives clues as to when the piece was written? How does the articulation affect the character? What about the music lends itself to the style it is written in and does it deviate in any way? Simply by having awareness of the many musical features that a piece has beyond a cluster of notes, you will become more musically literate.

When played well, music oozes with character. It is up to you, the performer, to bring out that character, something that you can’t do if you are unsure what it is. Think of characteristics that you would use to describe people, such as “playful,” rather than musical features such as “fast.” Below is a list of musical characters to give you a starting point.

Playful

Joyful

Bright

Cheerful

Heroic

Triumphant

Majestic

Tragic

Stealthy

Brooding

Evil

Creepy

Angry

Fierce

Driven

Passionate

Consider each of these words and try and think of a piece of music with its character. What about the music gives it its character? It is only when you ask this question that you can truly appreciate the diversity of music that has been composed.